What is ALS? How do I talk about it?

“I know that it starts, like it has steps, and some people it affects their lower bodies, often it’s both. Well, for my mother it’s both parts of the body.”

What is ALS?

ALS is sometimes called “motor neuron disease,” or MND. This is a better description of what happens in the body. We are going to get real detailed, so hang on.

First, the nerve cells that communicate (innervate) with muscles are diseased and die. However, this term, MND, is used less often because there are other causes of MND besides ALS (in other words, MND does not refer only to people with ALS). ALS is a type of Motor Neuron Disease (MND).

What are MNDs?

MNDs are diseases that damage the motor nerve cells, which are cells required for movement. Amyotrophic is a medical term meaning loss of nutrition to the muscle. Muscles lose their bulk and get smaller.

The term sclerosis means scarring or hardening. In ALS, this scarring is due to the damage and loss of nerve cells. Lateral means the side and refers to the area of the spinal cord that houses the fibers of the nerve cells that die off in ALS.

What does ALS do?

ALS causes weakness and wasting of all voluntary muscles. This means that the muscles we use to move, swallow, and even breathe, become affected by ALS.

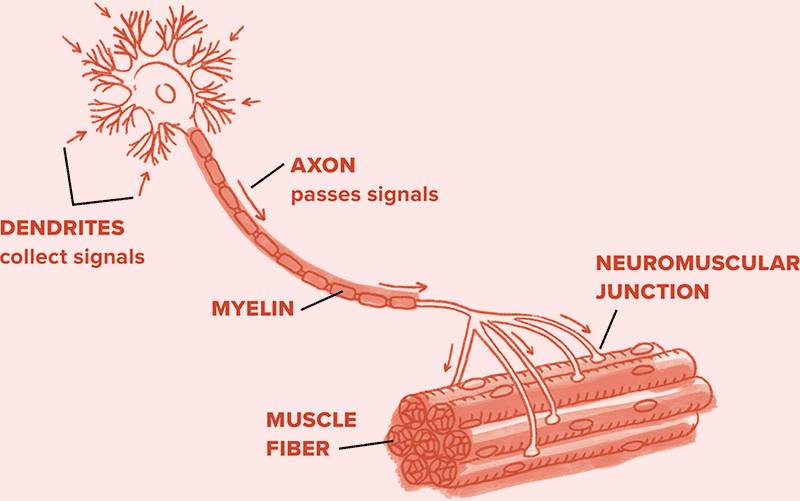

All body movements require nerve cells in the brain and in the spinal cord. These nerve cells are called motor neurons and they control our muscles. The brain sends signals to the appropriate nerve cells in the spinal cord that control the muscles in the arms, legs, and feet, for example, to perform actions such as picking up a glass or moving a foot. These cells send messages to the muscles via a long nerve fiber called an axon.

Without this signal, there is no way for a muscle to know what to do. It is similar to computer keyboards: if they are not plugged in, there is no connection and the computer screen remains blank. The muscle also needs this nerve connection to survive.

There is a symbiotic relationship (that means they need each other) between every muscle in our body and a specific nerve axon. If the connection is severed, not only will the muscle not get the signal of what to do, it also will shrink (medical term: atrophy) without an axon (Figure 2). This is why, in ALS or other MNDs, we cannot stimulate the nerve artificially to reverse the effects of the disease: the axon must be intact for the muscle to remain healthy.

Is ALS everywhere in the body?

The disease can start in different places in the body. However, as time progresses, the weakness worsens in the muscles that were affected first and then spreads to other parts of the body.

What causes ALS?

ALS most often occurs sporadically, meaning without a known cause or warning. There is no known direct cause. That means we can’t say if it has to do with what you eat, how you exercise, or the air you breathe. But, there is a lot of research being done to figure out what factors in the environment may influence how someone develops ALS.

If we don’t know what causes it, how do we know who will get it?

Sporadic ALS is responsible for approximately 90 percent of all cases of ALS diagnosed. Sporadic means the disease is not passed down in families. Researchers are looking for genes that may make one person more likely than another to develop ALS.

There is a small group of people with a genetic form of ALS, referred to as familial ALS or fALS. This makes up approximately 10 percent of people with ALS, and it has a high presence in the family (medical term: penetrance). This means that many family members are affected by it (such as parents, siblings, or grandparents; but not typically a second or third cousin, or remote family member). However, if you have concerns about a family connection, you should speak to your physician or health care provider to discuss the potential of developing fALS and any recommended genetic testing.

How does ALS get worse?

This is a tough one to answer, since no two people experience ALS exactly the same. Some people have it worse and decline in one area before it spreads, while others have a rapid progression throughout their body. In some people, the disease progresses very slowly.

How long does someone live with ALS?

In general, people with ALS live about three to five years after they experience the first sign of weakness. This is a generalization, which is based on averages. People with ALS can live anywhere from a few months to decades depending upon disease changes and the types of medical care and assistive devices they choose. ALS is different in each person and will run an individual course.

So, what happens in ALS?

A person with ALS may develop severe weakness (the medical term is paralysis) of all muscles in the arms and legs, and the muscles of breathing, swallowing, and speaking. But remember—every person is different.

Some people have severe weakness of one area, but little in others (for example, they may be unable to swallow but still able to walk and drive), but other individuals may demonstrate a similar severity of involvement of different areas. Some people have the disease and it progresses very slowly, while others have changes that happen more quickly.

It is very difficult for doctors to predict how a person’s ALS will progress at the time the diagnosis is made. So, they try to see the person with ALS as much as possible so they can watch and track how the symptoms progress.

Can you tell us anything about what may happen next?

Although no ALS health care provider can know for sure, it is generally true that individuals who experience a more rapid onset will have a more rapid course of the disease, while individuals with a slow onset will likely experience slow progression. In general, people with face and tongue (the medical term is bulbar) involvement have a shorter life span due to the problems with loss of function in this area (breathing, swallowing).

It is also generally true that the spread occurs from one body part to the next. So, for instance, if the disease starts in the legs it would be expected that the arms would be affected next. Symptoms do not begin all at once or suddenly.

How fast can the changes happen?

Many people fear that they will wake up paralyzed, but symptoms do not change overnight. Some family members may notice an abrupt change, but that change is likely due to the person living with ALS trying to compensate for the things they can no longer do. They just can’t do them anymore, so it looks like they changed really, really fast.

Is there anything we can do to help with the changes?

Well, keep any eye out for changes. No, you don’t have to stare at your family member with ALS, but just notice when things change. Then let your mom or dad know and they will tell the doctor. That way the doctor may be able to treat the symptoms and prepare you for upcoming changes.

I know things change—I do a lot to help my dad

Yes, that is true. People with ALS will lose the ability to do a lot of things, including getting out of bed, moving onto a chair, getting dressed, showering, eating, and toileting. This is due to the loss of the motor neurons causing paralysis. Also, people living with ALS lose muscle mass and, as a result, lose body weight. Weight loss is also due in part to increased need for calories, decreased ability to eat adequately because of swallowing difficulties, as well as arm and hand weakness, which impacts the ability to feed oneself.

Is there a cure?

Unfortunately, there is no cure for ALS. There is no known way to stop or reverse this disease. There are, however, treatments that ALS specialists recommend to help people manage their symptoms.

The above is a tough section full of details, bizarre terms and lots of information. After reading it is a great time to stop and ask more questions of your parents, doctors, or your local ALS Association chapter staff.

ALS can be pretty confusing, so the best thing to do is ask. If you are not sure what to ask or how to talk about ALS, the next section is just for you!